The company that has continuously produced high-quality games since the age of microcomputer – Nihon Falcom Corporation has made a donation of a dead stock of floppy disks used for user support to us.

The disks we received included Ys, which is celebrating it’s 30th anniversary this year. The total number of disks we received is 262. These disks were backups that were distributed to users who could not play the games they bought because their copy was defective or bugged. Which means that all the titles in the collection are completely bug-free copies. Also, they are all unused and clean copies without user saves.

The Nihon Falcom Corporation style meant not only producing quality games but also a high regard for the company’s history. The condition of the collection we received reflects this philosophy. The 262 floppy disks we received will be preserved in our archive room as an important part of Falcom’s history livening up Japanese gaming.

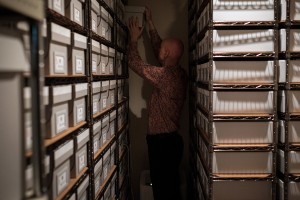

Our archive room is specially designed to maintain temperature and humidity and to reject any source of damage from sunlight and magnetism. To prevent the degradation of the documents, we use a specially designed container, jointly designed with Archival Conservation & Enclosures Co., Ltd., so that the documents are confidently passed down to the next generation in good condition. Furthermore, to prevent the complete loss of data due to degradation, we will use specialized equipment to digitize the data in the floppy disks. These 2 steps are made to prevent the loss of documents in our care.

This donation is a very meaningful one to us. Nihon Falcom Corporation, one of the creators of what we aim to preserve, has placed their trust in us by giving us their documents. We will work even harder to increase the documents in our care, whether it is for one more, or for a day longer.

We are preparing our archive room for public viewing. We are constantly working hard to build an archive that can contribute to students of gaming history and creators alike, but we still lack the people and resources. To open our archive room to the public, which houses over 10,000 80s~90s PC games, we need your help and support. Please do help us if you like our work.

* Those interested in pledging contributions may do so here. *

Game Preservation Society, Joseph REDON

Photos, Nicolas DATICHE (http://nicolasdatiche.com/)

Translated by Ming TEE